Eight Planning Ideas In The Age Of COVID

By: Randall A. Denha, J.D., LL.M.

At this unprecedented time, we are all grappling with the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on our families, health care system, educational system, and the economy at large. As with past economic downturns, when asset values are depressed and interest rates are low, there are a number of strategic estate planning opportunities that actually become more powerful in this difficult environment. Setting up these structures now could save your family significant estate tax dollars once global markets have stabilized and rebounded.

Under current law, the federal gift, estate, and generation-skipping transfer (“GST”) tax exemption amount for 2021 is $11.7 million per individual or $23.4 million for a married couple and increase by inflation each year, but only until January 1, 2026, when the exemption amounts will automatically be reduced effectively by 50 percent. Now is the perfect time to maximize gifts to your family, as the current U.S. tax law allows for a historically high gift and estate tax exemption. The Biden campaign proposed an immediate reduction in the estate and GST tax exemptions to $3.5 million per individual or $7 million for a married couple and a reduction of the lifetime gift tax exemption to only $1 million per individual or $2 million for a married couple.

These changes could legally be made retroactive to January 1, 2021, though most tax professionals believe that any such changes will be made prospectively—either effective at a later date (for example, later in 2021 or perhaps on January 1, 2022), or when the change is first publicly introduced in Congress. If the changes are not made by the end of 2022, it is likely, given the general political climate, that the automatic reduction will take place as scheduled on January 1, 2026.

However, with the upcoming election, this could quickly change. The gift and estate tax exemption could fall, or tax rates could increase — or even both. Our advice is to take advantage of a good thing while it’s here. Don’t wait until it’s too late

With that background in mind, here are several ideas to consider.

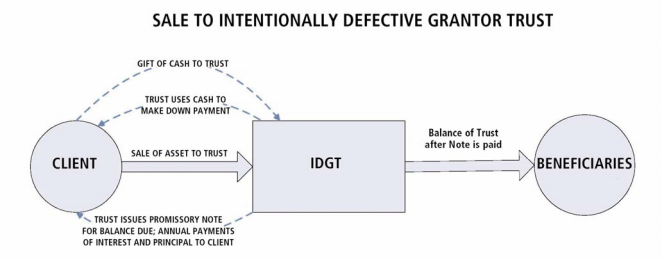

- Utilizing an Intentionally Defective Grantor Trust (“IDGT”). The structure of a typical IDGT transaction involves both a gift and a sale of assets.

- Gifts to an IDGT. When an individual creates an irrevocable IDGT and transfers assets to it, that individual ceases to be the owner of those assets while continuing to be responsible for any income tax owed on those assets. In this manner, a transfer to an IDGT removes that property from the transferor’s estate for federal estate tax purposes but is a non-taxable event for income tax purposes. The transfer is a gift for federal gift tax purposes, which would be reported on a gift tax return and would utilize a portion of the transferor’s lifetime estate and gift tax exemption. No gift tax would be owed if the exemption used is larger than the value of the transferred property. In addition, transferring assets at their currently depressed values allows for more asset growth to occur within the IDGT (i.e., outside of the transferor’s taxable estate) and potentially saving the transferor’s estate approximately $0.40 of estate tax on every dollar of growth (under current federal estate tax laws). The income tax attributes of an IDGT are also advantageous because a transferor can further reduce the value of the transferor’s taxable estate by continuing to pay the income taxes attributable to the transferred property. The trust itself can benefit the transferor’s children, or others, pursuant to the transferor’s wishes.

- Sale to an IDGT. Another option is for an individual to sell assets to an IDGT in order to take advantage of the current, historically low interest rates. A simplified explanation of a sale is as follows: (1) the transferor sells assets at their currently depressed fair market value to the IDGT in consideration for an interest-only promissory note with a balloon payment due after a set period of time; (2) the IDGT can utilize the income from the assets transferred to make payments on the note. A sale does not utilize a transferor’s lifetime estate and gift tax exemption because the transferor is swapping an asset for a promissory note of the same value. The value of the transferor’s estate remains the same immediately following the sale. The goal is that when the promissory note balloons the transferred assets will have grown in value exceeding the note’s interest rate. Again, any asset growth exceeding the note’s interest rate could save the transferor approximately $0.40 of tax on every dollar of growth (under current federal estate tax laws).

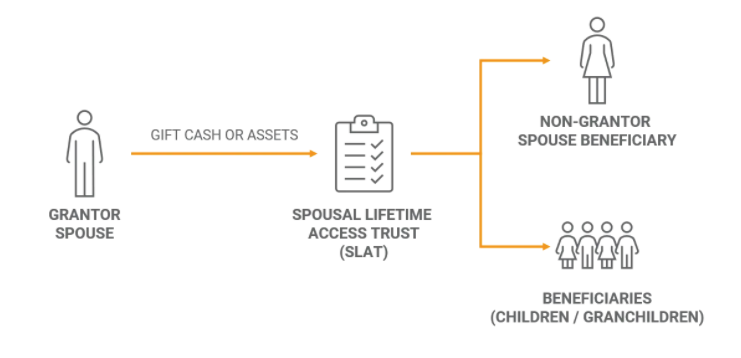

2. Utilizing a Spousal Lifetime Access Trust (“SLAT”). A SLAT can be established in much the same way as an IDGT with one primary difference—the transferor’s spouse is the initial beneficiary of the SLAT during his or her lifetime. This creates a safety net for the married couple because the SLAT can distribute payments to the spouse for specific purposes if there is an economic need. After the spouse’s lifetime, the trustee would generally allocate the remaining SLAT assets to a separate trust or trusts for the benefit of children and more remote descendants of the transferor. Again, the transferor would utilize a portion of his or her lifetime estate and gift tax exemption to fund the SLAT. Like the IDGT, a SLAT may also be funded by a sale of assets in exchange for a promissory note, and the transferor could continue to pay all income taxes attributable to the SLAT property. Here is a schematic of the structure:

3. Installment Sales. An installment sale is a sale of property where at least one payment is due in the tax year after the sale. More typically, installment sales are structured over a series of payments, spreading out the cash flow for buyer and seller. Importantly, as seller, it also spreads out the tax consequences for the sale as you recognize the income for tax purposes in the year you receive the money. Common examples include the sale of real estate, a privately held business and even an interest in a family business. However, you cannot use an installment sale for investment securities, property sold by a dealer, inventory, or property sold at a loss. In an estate planning context, you can use an installment sale for appreciating assets to freeze their value and remove future appreciation from your estate. Importantly, it does not reduce your lifetime gifting exemption. If you’re selling an income-producing asset, you can spread the payments in a way that helps the buyer afford the property. As a result, it can serve as a mechanism to transfer assets to less affluent children or other family members who might not otherwise be able to afford the purchase. The sale must include interest at a minimum rate established by the IRS — based on the AFR — or the IRS will treat a portion of the gain as interest. The interest is considered ordinary income while the gain on sale is generally a capital gain, taxed at lower rates. As a result, the current low interest rate means that you can charge less interest on the sale without the IRS intervening.

4. Self-Cancelling Installment Sale. A self-canceling installment sale is an installment sale with a provision stating that the obligation is considered to be paid in full upon the death of the seller. The sale must include a premium in terms of the selling price or interest rate, reflecting the fact that the seller’s estate may not receive the full amount of the sale in the event of death. Ideally, this strategy saves estate taxes. Upon the seller’s death, the note cancels and the seller’s estate is substantially reduced for estate tax purposes. However, as a result of the cancellation, the estate must recognize the remaining deferred gain for income tax purposes.

5. Intra-Family Loans. If you cannot or would prefer not to make an outright gift to a family member, you might choose to loan the funds instead. Here, too, a down economy provides a benefit as the IRS’ rate for short-term intra-family lending is at a historic low. The IRS requires a minimum interest rate on a transaction between family members or other related parties before it considers the transaction to be a loan and not a gift. Provided the loan’s interest rate is at or above this minimum rate and the recipient is credit-worthy, there is no gift tax. Of course, at some future date, you might choose to forgive some or all of the balance of the loan as a gift. Minimum federal interest rates for tax purposes, as established by the applicable federal rate (AFR), are near historic lows. As a result, it may be advantageous to renegotiate your higher-interest related-party loans. If you have an undocumented loan, this might be the time to formalize it with a promissory note. Without documentation, the IRS may consider your loan to be an outright gift. If you are planning a new related-party loan, the low minimum interest rate may make this an attractive time to complete the transaction. If you create a new term loan now, when the AFR is near an all-time low, you can lock in a very favorable interest rate. In April of 2021, the annual short-term AFR (for notes of three years or less) will be 0.12 percent, the mid-term AFR (for notes of more than three years and up to nine years) will be 0.89 percent, and the long-term AFR (for notes of more than nine years) will be 1.98 percent. Thus, depending on the length of the loan, the interest paid by the donee family member on the intra-family loan could be very little. The borrowed funds could be used by family members to invest in assets that outperform these low interest rates, thereby moving value into the estate of the younger generation. Finally, for those clients who have already made full use of their lifetime gift exemption, an intra-family loan is a great way to transfer additional assets to their family members.

6. Grantor Retained Annuity Trust (“GRAT”). For individuals who have utilized a majority of their estate and gift tax exemption with prior gifts or who are not financially ready to make outright gifts, an irrevocable GRAT can be used to potentially transfer future growth on currently depressed assets to children. Upon a transfer to a GRAT, two property interests are created: (i) a present annuity interest payable to the transferor for a minimum of two years; and (ii) a remainder interest that passes to the GRAT’s beneficiaries (typically the transferor’s children) following the annuity term. The trust can be established with a remainder interest value near zero for gift tax purposes, which means little federal gift tax exemption is needed to establish the GRAT. In general, if the GRAT’s assets appreciate at a rate greater than the IRS’s defined rate of return (1% for a GRAT created in April 2021), then that appreciation above the IRS’s rate of return would pass to the remainder beneficiaries free of estate tax. In addition, GRATs can be structured to use little or no lifetime gift credit. An individual may also use a GRAT, which is most effective in a low interest rate environment when asset values are low. A GRAT is a type of grantor trust that permits an individual to transfer assets to a trust and retain an annuity interest for a defined term. At the conclusion of the trust term, the asset appreciation in excess of the annuity payments made to the grantor passes to the designated beneficiaries. The required annuity payments are based on several factors, including the applicable interest rate in the month of the creation of the GRAT. As the interest rate decreases, the required annuity payment is lower, providing a greater chance that the assets appreciate in excess of the retained annuity payments.

7. Direct Gifts and Gifts to 529 Plan Accounts. Not all gifts require an irrevocable trust. For instance, a direct transfer of depressed stock or other depressed assets to children or grandchildren may be suitable in a given situation. If flexibility is important, a gift to a 529 plan account for the educational needs of a child or grandchild may be an option. A transferor can pre-fund up to five years of annual exclusion gifts (currently $15,000/year) in a single year per beneficiary (i.e, $75,000 in 2021).

8. Conversion of Traditional IRA to a Roth IRA. If you plan on transferring any traditional IRA balances to non-charitable beneficiaries upon your death, you might now consider converting your traditional IRAs to Roth IRAs. Converting all or a portion of a traditional IRA account to a Roth IRA at a time when your account balance is down has two advantages: (1) the timing of the conversion at lower valuations minimizes the ordinary income taxes due upon the conversion; and (2) the timing also allows for future growth of converted assets to occur tax-free within the Roth IRA account. In addition, unlike traditional IRAs, the Roth IRA is not subject to required minimum distributions beginning at age 72. Earlier this year, the Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement Act (SECURE Act) significantly changed the planning strategies associated with individual retirement accounts. For inherited IRAs, the SECURE Act now requires that most inherited IRAs must be liquidated within 10 years following the death of the IRA owner. Roth IRAs are not immune to the forced liquidation of the 10-year rule.

However, Roth IRAs are not subject to income tax upon liquidation. The beneficiary of a Roth IRA will never have to pay income tax on the growth inside of the IRA during the 10-year period and will never have to pay income tax on the liquidation of the IRA during or at the conclusion of the 10-year period. If an individual owns a traditional IRA, the individual may convert his or her traditional IRA into a Roth IRA during his or her lifetime.

The conversion is treated as an income taxable event to the individual. Ideally, the individual would pay the income tax incurred on the conversion out of non-IRA assets so that the full converted IRA could grow income tax free. The SECURE Act has highlighted a planning dilemma whereby an individual may either convert his or her IRA to a Roth IRA and pay the income tax on the value of the IRA on the date of the conversion or keep his or her “traditional” IRA and the owner’s beneficiaries will pay the income tax during the 10-year period after the IRA owner’s death. In an environment where IRA values may be expected to appreciate, a Roth conversion would enable an individual to pay the income tax now on the low value so that if the value of the IRA appreciates and returns to its pre-coronavirus level, the appreciation will be tax-free, and the beneficiaries will not pay any income tax when they are ultimately forced to liquidate the inherited IRA at the conclusion of the 10- year period after the owner’s death. Of course, there is no way of predicting future values or how much of the IRA might be depleted over the owner’s lifetime.